THE AMAZING MIZZEN

©

2010 Tor Pinney - All Rights Reserved

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ |

Ketches and yawls are not as common as they once were.

Still, mizzens have been around for a long time and with

good reason. A mizzen sail can be useful in ways that many

modern sailors don't realize. Positioned so far aft, this

little workhorse acts as a big wind rudder, pushing the

stern away from the wind and forcing the bow the opposite

way.

There are occasions when this can be particularly useful.

The

Riding Sail

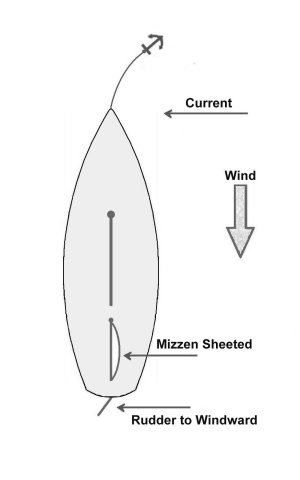

When

anchored in a gentle crosscurrent, a boat may turn

broad or even broadside to the wind. This can be inconvenient if the sea

is rocking the boat or if you want the breeze to flow

through the hatches.

With

a mizzen it’s easy to bring the bow into the wind. Hoist

the mizzen sail and sheet it in hard. As long as there is

sufficient breeze, the "wind rudder" effect will overcome

a moderate current and head the boat into the wind and sea.

Cocking the rudder to windward will help, too. (See Figure

1)

Even

in normal anchorage conditions, holding the bow

steadfastly into the wind reduces strain on the rode

and anchor compared to a vessel that yaws or "sails at

anchor," thus lessening the risk of chafe and dragging. |

|

Another advantage to

leaving the mizzen up when anchored is readiness for the

unexpected. If for any reason the boat should drag or come

adrift, a mizzen sail holding the bow close to the wind

gives the skipper better control - some ketches may even

tack under mizzen alone, or do so making sternway combined

with a cocked rudder. In any case the hoisted mizzen sail

buys precious time to either start the engine or hoist a

headsail to get the boat underway and under control.

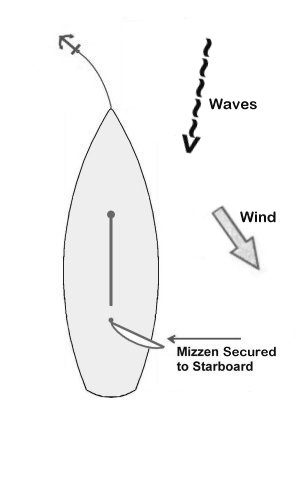

If a swell is

working into an anchorage at an oblique angle to the wind,

rocking the boat uncomfortably, use the mizzen sail to

head either the boat's bow or stern closer into the surge.

Simply secure the mizzen boom out to port or starboard

with a preventer. This will hold the boat at its own

oblique angle to the wind, lessening or even negating the

angle of the swell. The boat will roll less and the taut

mizzen sail will dampen what little roll remains.

(See

Figure 2) |

|

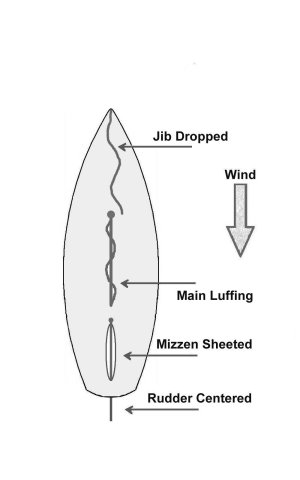

Anchoring

Once

the anchor is lowered and the boat begins making sternway,

most boats quickly fall off broadside to the wind. If

the mainsail is still up it may fill, and off she goes

sailing on her anchor. In a crowded harbor this can be

problematic. Even if the mainsail is doused, broaching

while anchoring is awkward and unseamanlike. It seems to

take forever for the boat to straighten herself.

The

solution is to keep the mizzen sail sheeted in tightly

when anchoring. The "wind rudder" effect will hold the bow

to the wind even as the boat drifts back. Anchoring

becomes easier, neater, and safer with a mizzen. (See

Figure 3)

You

may then set the anchor without the engine by backing the

mizzen as in Figure 2, thus putting pressure on the hook

so you can feel it's dug in.

|

|

|

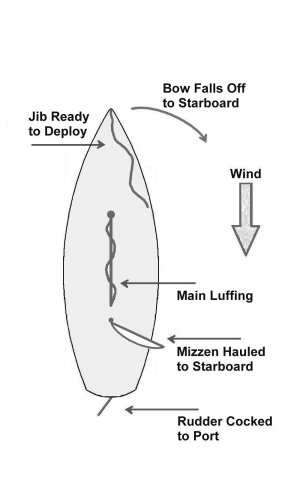

Weighing Anchor Under Sail

In

moderate conditions it's fun and easy to get underway

without firing up the "iron jenny". First, shorten your

scope by about half. Next hoist the mainsail, leaving the

sheet slack so the sail is luffing, and have the jib ready

to run up or roll out on the intended lee side. Then weigh

anchor. Once the bow falls off the wind, set the jib and

sail away!

However, in close quarters you need to control which way

the boat falls off. Solution? You guessed it - the mizzen.

By keeping the mizzen sail sheeted in hard at first,

you're sure to have the boat pointed into the wind when

the anchor breaks free. Then quickly release the mizzen

sheet, grab hold of the mizzen boom and push or pull it

over to the side towards which you want the vessel's bow

to head. (You can rig up a block & tackle in advance to do

this without straining any muscles.)

For

example, suppose there's a boat anchored close by to port,

so it's essential to sail off to starboard. Push the

mizzen boom out to starboard. The wind strikes the mizzen

sail, pushes the stern to port, and presto! The bow falls

off to starboard. Be sure that the rudder is amidships, or

else aimed to port if the boat starts making sternway.

(See Figure 4)

|

With practice you can actually

back the boat straight astern for quite a distance under sail to

get out of a crowded spot with vessels moored to both port and

starboard, using the mizzen and the rudder to steer.

Heaving-to

There's no single correct way to

heave-to in heavy weather. Each boat handles differently, but

the end result should be the same. The vessel should lie at a

relatively safe and comfortable angle to the wind and sea,

typically with the bow pointing between 40° and 60° off the

wind. On a ketch or a yawl, all other sail can often be handed

and the mizzen sheeted in, reefed if necessary. The helm is

usually secured amidships or nearly so. The "wind rudder" effect

does the rest, holding the bow to windward while the bow's

own windage holds the vessel in balance.

And More

A mizzen sail allows a boat to

carry the same sail area as her sloop-rigged sisters while

reducing the size of the mainsail. A smaller mainsail is easier

to hoist, reef, and furl. A shorter mainmast reduces weight and

windage aloft, increasing stability. A split rig also allows

instant reefing. When the wind kicks up you simply drop the

mainsail and continue sailing, uninterrupted, under the

beautifully balanced combination of jib and mizzen, or "jib 'n

jigger" as the old salts call it.

A mizzen increases your

selection of sail combinations in other ways, too. There's the

easy-to-handle mizzen staysail for reaching in light airs. This

sail is like a free-flying jib or drifter except that its head

hoists to the mizzen masthead, its tack secures just abaft the

base of the main mast or perhaps to a padeye near the windward

grab rail, and a single sheet leads through a block at the end

of the mizzen boom. Downwind in light airs, some ketches even

fly mizzen chutes. Of course, you can always hand the mizzen

sail entirely and sail the boat as a sloop or, if she carries a

staysail, as a cutter. This is especially true of the yawl,

which is virtually a sloop with a mizzen added. This "sloop

option" can be effective sailing hard to windward when the air

coming off the main may luff the mizzen sail.

In port, the mizzen boom can

serve as a ready crane for launching and lifting heavy items

such as the dinghy's outboard motor.

Some skeptics describe the

mizzenmast and rigging as "something to lean against in the

cockpit". Well, they have got a point. It does provide solid

handholds and a convenient place to clip your safety harness.

It's also an excellent mount for a wind generator on a swivel

base. Some blue water voyagers mount a spare VHF antenna at the

mizzen masthead, in case lightening or dismasting renders the

main masthead installation useless.

Which raises this point: If a

sloop is dismasted and the spars lost at sea, there had better

be enough fuel aboard to motor home. On a ketch and even a yawl,

you can still set a mizzen sail and mizzen staysail. They’ll get

you there eventually.

The sloop is

generally the most efficient to windward and the cutter rig is

supremely practical offshore. Happily, those sail configurations

are still available to a double-headsail ketch or yawl simply by

furling the mizzen. But as we have seen, when that mizzen sail

is set it truly does have many uses.

~

End ~

Back

to List of Tor's Tips